|

Gullah Food

|

|

|

Gullah Food is older than the South and as ancient as the world. It is one of the oldest African and American traditions being practiced in this country today. As it has always been, it is informed by need,availability and environment. The Africans brought to the Carolina colony used the similarities between culinary environments of the low country and the West Coast of Africa to create a food culture that has come to characterize the regions where they live. One of the biggest ironies is that rice, the grain that had been in African food culture for thousands of years, became the cash crop and reason for the American enslavement of many Gullah people. For years, the oceans, other bodies of water, and farming practices remained in the backdrop while rice, seafood and vegetables (corn, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, collards, turnips, peanuts, okra, eggplant,beans and peas) brought the connection between both sides of the Atlantic full circle. Slave cooks simply adapted their African cooking traditions to American soil. Even today, cooking traditions remain somewhat consistent. One pot dishes, deep frying, rice dishes, sea food, boiling and steaming, baking in ashes, basic and natural seasonings, and food types consistent with those received in the weekly rations on plantations are all characteristics of Gullah food. The food is characterized by the ever presence of rice and a distinct “taste” present wherever Gullah people are cooking. The recipes are simply frames; the art work is created in the taste buds of the preparer. Try to obtain a recipe or cooking directions from Gullah cooks, and you will more than likely get the generic response, “ah ‘on measur.” They will tell you that they cook “cordin’ ta taste.” This taste is passed down from generation to generation, but unlike other ingredients, it is an elusive quality guided by memory and taste buds, almost impossible to explain in words. It is an ingredient that must be experienced. Tasted first, then duplicated each time Gullah food is prepared. Under the task system used on most rice plantations, each slave was assigned a certain task each day. These tasks included ground breaking, digging trenches, plowing, hoeing, harrowing, threshing and other specific tasks related to rice farming. Unlike gang labor employed on cotton and tobacco plantations, when slaves on rice plantations finished their assigned tasks, they were generally free to tend their own gardens, fish or hunt for wild game. As a consequence, they were often able to enhance and supplement their ration supply with vegetables from their own gardens, natural seasonings, wild game, chicken, eggs and fish. These supplements also include leftovers given to them during hog killings. Feet, ears, entrails, jowls, heads and the like are still favorite meats for celebrations.

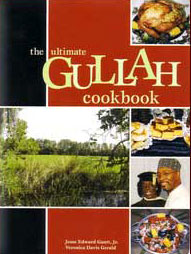

Slave cooks simply incorporated the weekly rations given to slave families into the African cooking traditions of their ancestors. A glance at the average food ration given on Brookgreen Plantation in Murrells Inlet in the 1800’s reads like a grocery list for a 21st century household. Simply speaking, Gullah food is about ancestral ties and American living, adaptability, creativity, making do, livin’ ot da waddah and on the lan’. It is a culture within the culture, with its own history, heritage, and distinction. It is a food culture handed down through practice more so than with words It lives among us in the restaurants, homes, kitchens, backyards, family reunions, church anniversaries, birthday parties and other celebrations that dot across the grounds that the Gullah call home. Excerpt from The Ultimate Gullah Cookbook by Jesse Edward Gantt, Jr. and Veronica D.Gerald |

|

|